BLUE LIQUID

December 5, 2020

Larch Tree

January 26, 2021They don’t tell you about the bedroom in Newark…

I was there, I swear. In my hospital gown, 2019, in between my Grandma Yola and Aunt Norma who were geared up in their jewel tone winter coats and silk scarves over the hair and tied around their chins. They were telling me I was okay. I’d been rolled into recovery from the ICU only hours before. Yet here I was, lying in my Grandma’s queen bed, aluminum closets on both sides, and the enormous kitchen only a door away. I was initially terrified that they had arrived to take me with them. And then shortly at ease to know they were maybe there to tell me I was doing great. I could smell the Stella Doro cookies dipped in coffee. It was a familiar smell.

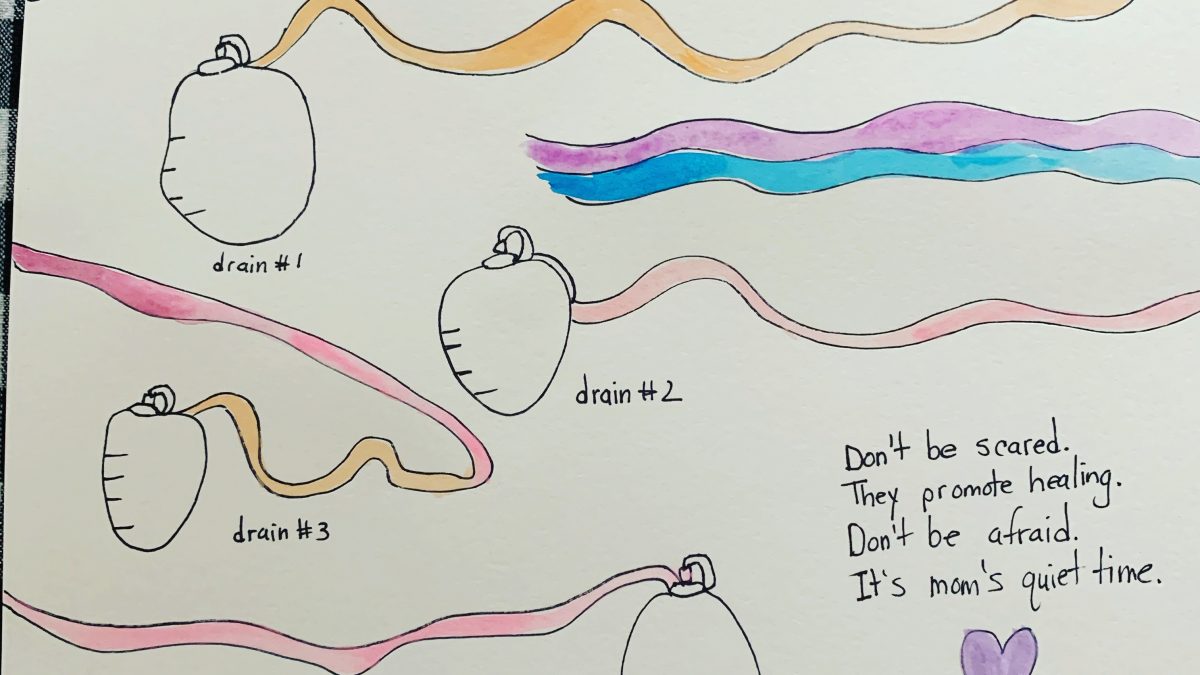

The nurses told me to take it easy, and call for help to use the restroom. I mean I was stitched up from hip to hip from where they grabbed my belly fat to make me new B cups, and then more stitches around each new breast. Four drains in my body and hanging from various openings, the drains situated in my gown pockets. My entire torso was compromised, but my legs and arms weren’t. So I didn’t call the nurses. I drank pitcher after pitcher of water. Okay, so I did call them for one reason—which was to hydrate me. But my hydration needs are and always have been tripled the average human, because when it comes to flushing, I go to extremes. Pitcher after pitcher I guzzled the water. Then every fifteen minutes I got up to pee, with no nurse’s help, because A. I was 42 and strong as hell and B. I didn’t want to bother them. They had enough work to do between checking my temperature every half hour, emptying my drains every few, and listening to the “heartbea”t of my new breasts, making sure everything was melding and connecting well. Then I hit a point where I just needed to breathe and relax. Use my Reiki breath and give myself a minute.

And when I did that, I got more than I anticipated. Now, who knows if it was the extreme amount of Tylenol and drugs they were pumping into my system, or my delirium from not having slept for real in days, but I felt my ancestors. I felt my beloved grandmother and her sister next to me. I heard their voices, and smelled their winter coats. The silk of their head scarves that smelled like lipstick if you can imagine that. I lay still and took it in. Breathe….Breathe….I don’t remember what they said to me. Their presence was enough. I like to believe they were there to remind me that in this moment of pure vulnerability and depletion, I was doing what generations of women before me have—healing and surviving in whatever way I saw fit for me..and that meant moving. So, I sat up, hyperventilated, and cried for the first time since getting out of surgery three days prior. I cried and cried, no matter how much it hurt my raw stitches. And the nurse came in. “This is very normal. It’s okay. You’re okay. You did it.” And she rubbed my back. I told her about my visit. She told me she believed me. She probably had to say that. After letting out the last of the sobs, I lowered myself back down, and closed my eyes. I think I got ten minutes of a nap in. The windows were wide open—because I insisted, as cold as it was. They commented that it felt like Denver in my room. I told them I need the cold air to feel better. They were okay with it all. This particular hospital was a teaching hospital in NJ, and I cannot say enough excellent things about their staff. Every single one of them. From the caretaker who bathed me because I begged for a shower. To the amazing Russian male nurse who made me laugh because he said my breast pulses sounded like a spaceship landing. I hope he fell in love by now. Any guy would be so lucky to have him in their life.

The visit, the cry. They were both essential to my healing because the next day I felt brand new. I still had barely slept a wink, but something about my existence felt real and like I was going home soon. I still couldn’t look down at my surgical work, but I knew the work felt tight, precise, and like it was done with so much love. I forever thank science and medicine for their work in the world. Good surgeons are artists and ultimate humanitarians.

If I focus, I can still go back to that bedroom in the Newark house that my grandma rented for years. The kitchen was the center, and the bedrooms lined the sides. She’d make my brother and I wagon wheel macaronis and take us to the local Italian market called Prosperity for candy of our choice. I guess the point of this is that we all need to figure out what it is that brings us toward healing. Ancestors, memories, belief in our bodies, whatever it may be.

Nobody tells you about that bedroom in Newark before you get rolled into surgery for twelve hours. And I’m kind of glad they didn’t.